Blog

Do non-human animals have beliefs?

Written by: Luuk Brouns

Meet Charlie, a six-year-old labradoodle. Charlie is a very energetic dog and is often chasing Maya, the neighbour’s Japanese bobtail. Usually, when Charlie engages in one of his many pursuits, he barks at Maya loudly and chases her throughout the neighbourhood, until Maya finds safety in the old oak tree, in Rebecca’s backyard. One day however, Maya seems to outsmart Charlie. The moment she spots him across the street, she runs into Rebecca’s backyard, and before Charlie comes rushing around the corner, she jumps through an open window. Charlie, not aware of what just happened, runs towards the oak tree and starts barking at it, as he usually does.

Rebecca, Maya’s owner, saw the whole event unfolding when drinking her morning tea in the sunroom. While see observes Charlie barking loudly, she mumbles to herself: “huh, Charlie believes that Maya is up in the tree, but he is wrong”. But what does Rebecca mean when she says Charlie believes this? Does Charlie truly have a mental state that has the content “that Maya is in the tree”?

In most of the literature regarding the philosophy of belief, a belief is defined as an attitude towards the truth or falsity of a proposition. This means that if you believe a certain proposition, you take this proposition to be true. If you believe that nothing travels faster than the speed of light, you take this to be true. Though other explanations exists, a common approach to belief is to understand the belief as residing in the mind. In a sense, we might say, a belief is a mental representation of what an individual thinks the world is like. So we might ask ourselves: is Charlie really capable of having beliefs? Or, more generally: are some non-human animals capable of having beliefs?

One contemporary answer to this question is the theory of Gradualism. This theory, established by Albert Newen and Tobias Starzak in their article How to ascribe beliefs to animals, holds that many non-human animals do in fact have beliefs in their mental repertoire. It is this article I chose to function as the foundation for my bachelor’s thesis. Here, I want to share with you the main ideas of a gradualist theory of belief, and two obstacles the theory is confronted with. These obstacles not only apply to the theory of gradualism but more broadly to our understanding of beliefs in non-human animals.

The Theory of Gradualism

A proponent of belief gradualism argues that beliefs are nothing more than informational states. Informational states are a specific kind of mental states and have two similar but distinct features. First, they represent the world as accurately as possible. Second, they represent how the world could be. These two aspects of informational states function as follows: imagine a chimpanzee, which is confronted with a peanut at the bottom of a vertically placed transparent tube, firmly secured in the ground. The chimpanzee, we might assume, sees the peanut at the bottom of the pipe and thus represents the world as such. The chimpanzee is hungry and wants to eat the peanut. He needs a way to get to it. Next to the chimpanzee is a bowl of water. If the chimpanzee really has informational states, the gradualist argues, it might be able to use the water in the bowl to increase the water level in the tube and get the peanut to float on top of it.

This might be considered a prime example of chimpanzees having informational states, for they seem to both represent how the world is and how it could be. And indeed, chimpanzees have often been observed to use water (or spit for that matter) to increase the water levels in order to reach certain food. And they are not the only animals to do so. Ravens have been observed to use rocks to increase water levels, and in a slightly different experimental setting, rats have been observed to find their way through mazes, in order to reach food. Some parrots even seem to understand the difference between red and blue objects. Such observations have led many scholars to conclude animals must have beliefs.

Such an outlook on the mental repertoire of non-human animals, might appeal strongly to many contemporary scholars. It did for me at least. This might be because I am highly curious about many different animal species and the relationship between humans and other animals. Furthermore, I feel a strong moral obligation to treat animals more justly. After finishing my thesis, however, I have concluded that the theory of gradualism is unable to fruitfully explain belief states in non-human animals. There are plenty of reasons for this rejection, but here I want to focus on two of them: intentionality and anthropomorphism.

Intentionality

Intentionality is the ability of the mind, or at least certain mental states, to be about something. This, like many philosophical concepts, might initially seem quite vague. So, what do philosophers mean by this? What is usually meant is that mental states, such as desires, doubts, motivations, and beliefs, can represent the world as being in a particular way. If I believe that the grass in my yard is green, that mental state is about the green grass in my yard. Beliefs are thus intentional states because they are mental representations that represent (or are about) certain objects, properties, or relations.

Ever since the introduction of the concept, many philosophical problems surrounding this concept have been raised. One of the major problems surfaces when one takes a materialistic stance. From this perspective everything is material or physical, meaning that everything in the world is subjected to the same natural laws and causally dependent. An explanation of intentionality should thus be able to explain how intentional properties are constructed from physical properties when physical properties do not have intentionality themselves. To put it in gradualist terms: how do informational states gain intentionality?

This question becomes even more pressing when we realize some philosophers argue that thermometers have some sort of informational state as well. Imagine a nice summer day sitting next to the pool. You look at the thermometer you brought with you and see it is 30 degrees. One might argue that the thermometer represents the information that it is 30 degrees outside. We might thus say this is some sort of informational state, because it represents the world in a certain manner. But thermometers are not usually regarded as having intentionality, let alone beliefs or any activity we would call “mental”. So, how should we understand this difference?

Unfortunately, the theory of gradualism does not provide a satisfying answer to this question. Therefore, it is a major problem for the theory as a whole. Gradualism is not alone in this however. Every realist material position within the philosophy of belief has difficulty accounting for the phenomena of intentionality. Some philosophers, however, argue that intentionality, difficult as it is, should not be the prime focus of inquiry into the mental states of non-human animals. We should instead focus on providing a scientifically relevant, experimental explanation by utilizing the data we have about animal cognition. Such endeavours, however, have problems as well. One major problem is the phenomenon of anthropomorphism.

Anthropomorphism

Anthropomorphism derives from the Greek words anthrōpos, best translated as “human being”, and morphḗ, meaning “form”. It thus means something like “the form of a human” and in modern terms means the attribution of human-like characteristics to non-human entities. We might, for example, think of the Greek pantheon, in which the gods all think and act like human beings. Or think about the books you read in your youth, where inanimate objects, animals, or monsters, behave as if they were human, or at least had human characteristics.

Notwithstanding the interesting and creative possibilities such a human ability might provide, for interpreting data regarding animal cognition this skill might prove rather problematic. Anthropomorphism is often regarded as a cognitive bias. A bias is a systematic error in our thinking, which influences how we perceive and interpret the world. When it comes to testing animal cognition, this means we might grant non-human animals certain abilities, which they do not truly possess. We thus project our abilities on the non-human animal.

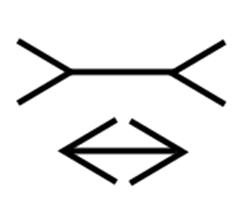

To stress the problem, think about the most widespread optical illusion: the Muller Lyer illusion. Initially, the horizontal lines of the different shapes seem to be different in length. But the length of the line is exactly the same in both instances. Despite the fact we know this to be true (because we can measure the length) they still seem to be of different lengths.

This is how one should think about the anthropomorphic bias as well. Sometimes it might seem that non-human animals have certain human-like characteristics, while they do not. This problem is even more pressing for mental states than it is for optical illusions. We can independently measure the length of the lines in the image, but it is difficult to independently measure mental phenomenon, because such entities are “inside” the animal, they are inherently subjective. The problem is thus not only that the anthropomorphic bias might cloud our interpretation of the data, but that we do not have a way of knowing if this is the case or not. Because there is to date no way to get around this problem of anthropomorphism, the interpretation of the scientific data proves obscure.

Charlie and Gradualism

So, should you now be just as comfortable to attribute belief states to Charlie? I would argue we do not really know if Charlie’s mental states (if he has any at all) have the property of intentionality. The main reason for this is that if we assume beliefs are informational states, then how do some informational states “get” intentionality? Without answering such a question, one has not confronted the problem of intentionality and leaves the reader without a full explanation of supposed beliefs in non-human animals.

We might want to observe Charlie more closely and try to infer from his behaviour what Charlie is and is not capable of. But beware. In interpreting the data collected on Charlie, we will likely fall into the trap of anthropomorphism. While cognitive biases cannot be overcome, they can be mitigated. I would thus propose a principle of caution: if interpretations regarding the mental states of animals might be subjected to anthropomorphism, which they to date always are, be conservative in ascribing them real mental states. I think it wise to abstain from any judgement regarding Charlie’s supposed mental states. The same goes for many non-human animals. While interesting research is being done on this topic, we should be wary of claims that exceed beyond what they can actually account for. And besides, Charlie, Maya and many more animals wills stay just as cute, fascinating or fun to interact with, whether they actually have believes or not.